Written by Nick Lovett who works in Public Policy, and Urban Transportation. This article first appeared on LinkedIn.

As someone who has followed the development of cities, business cases and public infrastructure investment for more than a decade in Christchurch and abroad, I have seen many examples of popular sentiment stray beyond the realm of economic rationality. The Christchurch Stadium as called for by the CERA blueprint has long been a concern in its ability to deliver the promised economic and social benefits outlined by the business case. While I agree that public venues such as stadiums, concert halls, and arenas are important for a city’s social, cultural and economic development, their benefits are often overstated by the cargo-cult mentality of their proponents while ignoring their zero-sum game economics. However, the job of local government is not solely to deliver projects upon a sound business case, under the Local Government Act, the purpose is two-fold:

-

to enable democratic local decision-making and action by, and on behalf of, communities; and

-

to promote the social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being of communities in the present and for the future.

Much like parks, libraries and swimming pools, stadiums may play a key part in helping Local Government fulfill its purpose. This is not to say that an indoor arena with 30,000 seats must be delivered as soon as possible, regardless of the cost. Regardless of what was said and done over the past decade, that facts are the scope of the project now exceeds budget affordability, meaning one or both will have to be adjusted. Many have called on the Council to get on with the project and accept the cost. This is a dangerous and fallacious sunk-cost argument that ignores current economic realities.

Mayor Lianne Dalziel recently outlined the facts in an opinion piece stating that the only alternative to proceeding with the cost is to pause and reevaluate. However, after waiting more than a decade, I believe that a central city stadium can be delivered much faster and within an affordable budget by making three strategic decisions:

-

Relocate and refurbish the temporary stands at Addington to the central city as ground and site preparation proceed over the winter in time for the 2023 rugby season.

-

Conduct a marginal cost to marginal benefit analysis and arbitration with the Crown regarding the need for a roof, while maintaining their commitment to funding $220 million of the capital cost.

-

Design the stadium so that the temporary stands can be progressively and incrementally replaced to form a complete, permanent, purpose-built rectangular stadium.

These strategic decisions focus on the scope of the project will not only remain within budget but deliver greater benefits over a longer period. The temporary Addington stadium has provided tremendous benefits for an extremely low cost. Over a decade, the initial 30 million investment has seen hundreds of thousands through the gates as it hosted several concerns, rugby games and festivals, with minimal operating subsidies. The option of building upon this strategy by relocating the stadium to the central city has not been explored to date because the site had not been cleared or prepared and it was always assumed a permanent stadium was financially feasible.

The 80/20 rule

There is a strong case to have a well-designed, centrally located stadium due to the agglomeration benefits, economic spillovers, and reduced transportation emissions. Furthermore, by virtue of being the most walkable accessible city in the country, event days would be enhanced by creating a better experience. The benefit of relocating the pitch, temporary stands and progressive build-out of a stadium as a ‘do-minimum’ means that 80% of the investment case benefits begin to accrue immediately for 20% of the cost. A sober analysis of the quantified benefits should closely examine how the marginal benefit of a $700million stadium (including 4-year construction time) vs the present value of immediately relocating the $ 30 million temporary stadium to the CBD over a summer.

Providing confidence and meeting the strategic objectives

The strategic intent of the Christchurch arena was to address:

-

address the Lack of frequent events in the CBD,

-

uncertain Private investment in CBD,

-

Christchurch’s identity as a sporting and cultural capital

-

the city’s event profile and ability to host large-scale events

None of these strategic objectives explicitly require a covered arena and it is unclear what was driving the need for an enclosed stadium in the first place. Multi-purpose arenas are an anachronism of the 1990s and have proven to be an ineffective master of none, and often disliked by fans when compared to specific-purpose, functional designs. The 2017 pre-feasibility study, overlooked the fact that any event revenue would come at the expense of similar events at Horncastle Arena. Furthermore, the rationale and case for a ‘multi-purpose’ covered stadium were not clearly articulated against the marginal cost in the 2019 business case. It is difficult to trace the origins of the need for a covered stadium, but it appears scoping for both 30k seats and an enclosed arena has driven the project beyond the realms of affordability.

To meet the objectives affordably, clever design and programmed investment can deliver benefits immediately, and a permanent structure over time as needed, and as municipal finances evolve. This approach meets many of the needs of revitalizing the CBD on the proven philosophy of activation, and incremental improvement that Christchurch has become famous for (Container Mall, Gap Filler etc.) In recent years, cheap, temporary stadiums have become much more common. Qatar has built an 80,000-seat stadium out of shipping containers and recycled steel to host The FIFA world cup in 2022. Using this design philosophy and low cost, low carbon methods in the interim should be examined more closely.

Reevaluating the need for a roof

Both the pre-feasibility study and business case as well as the CRFU and NZRU have repeated the need for a covered stadium. But what is unclear is any rugby rationale as the roof being a must, rather than a nice to have. Indeed, in an open letter to Council, Crusaders CEO Colin Mansbridge did not mention a roof, or covered stadium at all. Rather, the genesis of a coved arena seems to be Central Government, which has ruled out providing additional funding and not provided a rationale for requiring a fully enclosed stadium. From a sports perspective, data does not support the claim that covered stadiums draw bigger or more loyal crowds. Christchurch has a temperate and dry climate with a third of the rainfall of Auckland and half of Wellington. While a covered stadium may be preferred by fans, the willingness to pay a higher ticket price for the luxury is never factored into the equation. Capacity, not weather is cited by the NZRU as a hindrance to attracting test matches or large crowds and the two are mutually incongruent on a limited budget.

A quick review of the literature on the subject (at least for sports attendance) reveals that team loyalty, the closeness of competition, fan involvement, ease of access, and ticket price are the main attendance drivers. Forsyth Barr Stadium has often been cited as a benchmark, but the Highlanders have seen the largest decline in attendance from 2014-to 2017 out of any NZ franchise. Over the same period, the Crusaders had the highest capacity of any franchise despite the temporary nature of the stadium. By billing the proposed stadium as ‘multi-use’ it has obfuscated the fact that this will be used primarily as a rugby stadium. This is exactly how Dr. Michael Sam, an Associate Professor at the University of Otago characterized Forsyth Barr Stadium in an interview with Newsroom.

It is impossible to design a ‘multi-purpose’ stadium that will provide an exceptional experience for every type of event. Forsyth Barr’s roof negatively impacts the acoustics of live events. Queen’s Brian May described the structure as acoustically challenging. Built-for-purpose stadiums provide a superior experience, for example, compare the experience of watching cricket at the new Hagley Oval vs the former Lancaster Park. Contrary to popular belief, there has indeed been a trend toward specialization, rather than one size fits all in-stadium architecture, particularly in North America.

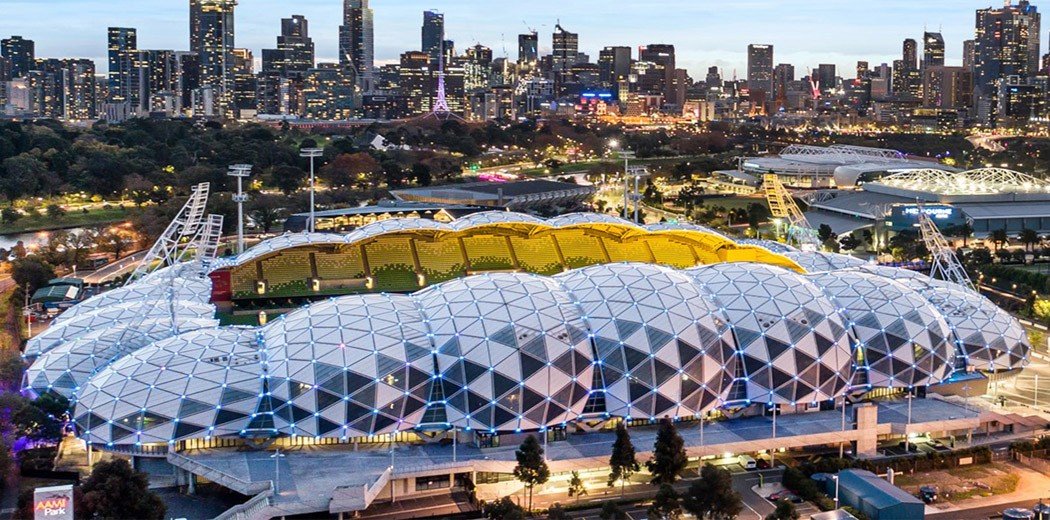

Closer to home, Melbourne’s award-winning AAMI Park completed in 2010 has been praised by players and fans for its innovative design and functionality. The purpose-built rectangular stadium has a capacity of 29,000 but was built with foundations capable of upgrading stands and capacity to 50,000 at a later date. As the home stadium for top-tier League, Rugby and Football Francises it has played host to Elton John, Phill Collins, Queen, and Taylor Swift without showing any ‘acoustical challenges’.

Indeed I think the CCC should be honest about the scope, needs and primary tenant in the design with a focus on rectangular turf sports. The Crusaders are one of the most successful professional franchises on the planet and as the anchor tenant, will reap many of the benefits of the stadium’s design. However, I do not think it is reasonable to ask them for capital contributions as this is a rare and unprecedented request. While a rectangular stadium can still be multi-use, it is important, to be honest about the fact that it will primarily be host to rectangular, turf-based sports. While in all likelihood it will be home to the Crusaders, there will be dozens of other events and sports codes hosted in the venue that do not necessitate a fully enclosed structure. Coming to terms with this will help build consensus around moving forward with an option and suitably refining the scope to bring it within an affordable range.

There have been talks about hosing one-off events such as Nitro Circus, but attendance records from Eden Park’s 2019 annual report show that crowds were roughly half that of a Wellington Phoenix match and accounted for less than 5% of the year’s attendance. When the Phoenix played in Christchurch at Lancaster Park in 2010, the crowd of 19,276 was, at the time, a record home league attendance for the Team so there is a strong case to cater the design towards these sporting codes.

We cannot afford to make a decision this hastily

In order to get the stadium’s design to fit the desired requirements, several aspects have been value-engineered out of the design to the detriment of surrounding land use and future opportunities. Removing the concourse level, and active edges in the cost design was a short-sighted choice to do too much with too little budget. This will reduce the amenity and economic productivity of both the stadium and the central business district in the long term. This is incredibly important so that the stadium does not become redundant while the debt is still being paid off. Stadium Australia (built for the 2000 Olympics) was nearly completely demolished in 2019 due to its obsolescence. Similarly, Docklands stadium in Melbourne has been described as a dead zone, requiring substantial urban design alterations to improve public access and revitalize the waterfront. Meanwhile, clever designs such as Little Ceasar’s Arena in Detroit have focused on designs that activate the street frontage and plazas to improve the fan experience and revitalize surrounding businesses.

There is good literature on regional economics vis-a-vis stadia development, we should draw on this to make sound, evidence-based decisions, not ones based on dogma and emotion. I’m hopeful that good advice can be obtained and for Council to make the best decision based on all reasonable and practicable options for the achievement of the objective of a decision as required by the Local Government Act.

Respected economists, as well as staff from the Infrastructure Commission, have highlighted similar cautions. Proceeding with the current scope and uncertain budget could end up being an albatross around the council’s financial neck for a generation. This would occur at a time when financial flexibility is needed most to deal with the effects of climate change on the city’s infrastructure. There will be a lot of pressure from people to ‘get on with it’ exposing the Council and ratepayers to risks and cost increases and protracted timelines. There is a smarter alternative that can deliver many of the benefits sooner, at reduced costs. North Harbour Stadium in Auckland has adopted this staged development approach to great benefit. Mixed-use opportunities, integrated development and integration with the public realm have all proven critical in maximizing benefits for the CBD, the city and the region.

A staged approach to construction and expansion is financially prudent and can deliver many of the benefits sooner than the ‘all or nothing’ covered stadium. I would urge the Council to pause and reconsider the scope while accelerating the activation of the site with a temporary relocation of the stands and pitch from Addington.